My older boys, Ford and Owen, then ages 11 and 9, were a mixture of nervousness and curiosity before U.S. Senator Susan Collins came to our house. My youngest son, Lindell, then 4, only wanted to know one thing: would she be nice?

My husband was on a year-long deployment overseas, and for each week that he was gone, we filled his empty seat at the dinner table with a new stranger. We hosted authors, musicians, school teachers, athletes, artists and even a zookeeper. We also hosted community and government leaders- - from both sides of the aisle.

The dinners were never about politics. Even if our guest wandered that way, the kids quickly brought him back to reality, usually with a question like, “Do you have any pets?” In one horrifying instance, Lindell mooned a governor. To be fair, he asked first, “Do you want to see something?” and the unsuspecting governor said, “sure.”

To my children, our guests were people, not Republicans or Democrats. They were someone’s mother, father, sister, brother, son or daughter. They had favorite foods, colors and music. And my boys judged — if I can use that word — them with the same criteria they did every other guest:

Are they nice?

Do they look me in the eye?

Do they talk to me like I matter?

Do they ask me about my dad serving overseas?

Some of our political guests were embroiled in heated debates or conflicts in their lives outside our dinner table. The boys didn’t care. Most of the time, they didn’t even know.

Governor Paul LePage, in particular, was making controversial headlines around the time we had dinner with him. Despite popular, public sentiment, however, LePage was one of my boys’ favorite guests. He played hide-and-go-seek with them in the governor’s mansion, and he told them his personal story of overcoming enormous obstacles (homelessness) to achieve great things. He made my boys believe they can do anything, and he let Ford sit at the head of the table.

Later, when the boys heard people talking about Governor LePage, they asked, “How can they dislike him? Do they even know him?”

I explained to the boys that people sometimes dislike politicians because of their politics. “It’s not personal,” I said.

And my middle son, Owen, said, “Of course it’s personal. They should hate the person’s politics, not the person.”

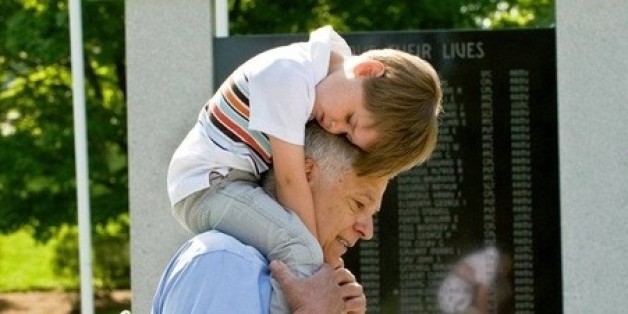

Our dinners had taught my boys (and me, through them) an invaluable lesson: when you’re gathered around a dinner table, even politicians with unpopular views or negative campaign ads are just, well, people. It’s hard to think of a senator as anything except absolutely human when you’re passing him the ketchup, showing him to the restroom or introducing him to your pet fish. And whether you’ve shared a table with a politician or not, it’s important to remember their humanness and to separate their politics from their person.

The only instructions I gave my boys before Senator Collins came to our door that night was this: “No potty humor.” I guess I’m a little embarrassed I didn’t prep them more, but in hindsight, my casualness allowed the boys to view Senator Collins as a woman, not a title. My youngest son sat in her lap, and he petted her hair and cheeks. To him, she was just a really nice lady.

The next week after Senator Collins’s dinner, we invited Lindell’s preschool teacher.

“Sure,” the teacher said, “but I’m no one important like Senator Collins.”

I smiled. “Are you kidding?” I asked. “Senator, schmenator. For Lindell, his teacher coming to dinner is like Elvis himself walking through the door.”

But the truth is, Senator Collins and all our political guests were teachers in their own way, too. And I will always be grateful for that.

NOTE: The year of dinner guests became the memoir Dinner with the Smileys, which O, the Oprah Magazine, called “uplifting” and USA Today called “all heart.”